I have always wanted to visit Washington, D.C., but I may never get there. My enthusiasm was somewhat dampened when, after 9/11, it was no longer possible to visit the White House. The fence that is now in place at the Capitol Building, following the breach of the building on the January 6th Electoral College vote, also makes it a little less inviting. Although the tall, intimidating temporary fence with rolls of barbed wire at the top has been removed, I believe there is still a smaller temporary fence around the perimeter that obstructs the former beauty of the Capitol Building. But there is much important symbolism of our history and our Christian heritage in Washington, D.C. There are a number of Scriptures inscribed in the buildings and monuments there. I’m grateful I was once able to visit Mt. Rushmore, to see the four giant presidential faces of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln carved in stone, towering above the Black Hills of South Dakota.

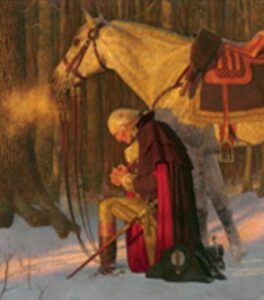

Recently I saw a sermon by a prominent pastor that was being streamed from Washington, D.C. He was taking a tour group from his church to learn of America’s Christian heritage. As he spoke, he stood in front of a portrait in the amazing, relatively new Museum of the Bible. He seemed overwhelmed by the quality and impact of the giant new museum. The original portrait behind him was temporarily on display at the museum. The painting is called “The Prayer at Valley Forge,” painted in 1975 by Arnold Friberg for the bicentennial. President Reagan had a copy of it in his office. It pictures George Washington in the forest of Valley Forge in winter, kneeling in prayer beside his horse. According to meetamerica.com, Friberg studied Washington’s army uniform at the Smithsonian and hiked into Valley Forge in February. He sketched part of the scene until his fingers began to feel frozen.

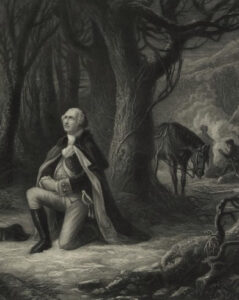

The internet tells us that there have been numerous paintings of Washington praying. Below are portions of three well known paintings portraying Washington praying at Valley Forge.

This is a portion of the painting by Friberg that was temporarily being displayed at the Museum of the Bible through May of 2021. The value of the original is said to have been estimated at $12 million.

This one, done in black and white, was painted in 1866 by Henry Brueckner. I have seen two versions wherein the figure of Washington was accented by colors.

This is a portion of the painting that was a collaborative work by Lambert Sachs(1818-1903) and Paul Gottlieb Daniel Weber (1823-1916). They were both Germans. Since Weber appears to be strictly a landscape artist, I assume the landscape portion was painted by Weber and the figures by Sachs.

The pastor who had brought his tour group to the museum began telling the story that inspired these paintings. The story says that during the desperate situation in which Washington and his soldiers found themselves at Valley Forge in the winter of 1777-78, Washington stole away to pray about the situation. His army had wintered over there—a location where they could keep their eye on the enemy but be far enough away to prevent a quick surprise attack. As the story goes, a man named Isaac Potts happened on the place where General Washington was praying and silently listened to his impassioned prayer.

I decided to do a little research on the details of the story. I discovered that some have wanted to dismiss the likelihood that the incident actually happened and have referred to it as a “myth” or “legend.” A website called UShistory was very helpful in supplying the sources of the story. The information on the website was derived from an article published by the Valley Forge Historical Society in 1945. I will summarize the information below.

(1) Potts’ version of the story made its first appearance in 1816, when Rev. Mason Weems wrote the 17th Edition of The Life of George Washington, with Curious Anecdotes.

(2) In 1850 Henry Woodman, who was born in 1795 in the old camp area, wrote the History of Valley Forge. His father was a soldier in the Revolution and was at Valley Forge. He stated that he didn’t know the accuracy of the details of Weems’ account, but he said, “I have heard the circumstances related and the spot was pointed out to me several years before I saw the account published.”

(3) Rev. Nathaniel Snowden, born in 1770 in Philadelphia, wrote a Diary and Remembrances that covered his youth and up to 1846. In it, he gives a long account, in his own handwriting, of Washington’s Valley Forge prayer. He states that he personally knew the Quaker named Potts who witnessed Washington praying alone in the woods. He says he got the story directly from Potts. According to Snowden, he himself was riding with Potts, who was a State Senator of the Whig Party at the time.[The Whig Party was founded in 1833 in opposition to the Democratic Party and emphasized the importance of Congress over the President]. Snowden told Potts he was surprised to find him friendly to the Patriots because most Quakers were Tories [loyal to the British]. Potts said he was once a Tory, thinking it impossible for the colonists to win over Britain. But “something very extraordinary” changed his mind. Then he proceeded to tell the story of seeing Washington kneeling in prayer, alone in the woods. He said “such a prayer I never heard from the lips of a man. I left him alone praying.” Potts then went home and told his wife about it. Snowden said he often saw Washington. Part of his comments were, “Washington was not only brave and talented, but a truly excellent and pious man of God and of prayer. He always retired before a battle and in any emergency for prayer and direction.” In Snowden’s account, he called Mr. Potts “John” rather than “Isaac.” Some accounts called Potts’ wife “Sarah.” He married Sarah in 1803, after the death of his first wife, “Martha.” (The writer of the article states: “The Rev. Mr. Snowden’s use of “John” and not “Isaac” in referring to Potts may easily be due to momentary lapse of concentration on a single item, as happens frequently among writers who possess the correct facts but neglect their importance at the moment.”)

(4) Potts’ biographer, Mrs. Thomas Potts James, lends support to the story. She had a paper signed by Potts’ daughter, Ruth-Anna. The account differs slightly in some details but is substantially the same.

(5) There is a very different story about Washington being found alone in prayer, as told by a former pension agent. It comes from a series about Washington and the Revolution published in a New York periodical called The Aldine Press in 1878. The agent had friendships with many men who had memories of the Revolution from their childhoods. He wrote recollections of conversations he had. His version of Washington’s prayer at Valley Forge is quite different. His account describes Marquis de Lafayette and General Muhlenberg as good friends. They both spoke French. The agent says that on January 17th the two had just visited troops at the hospital who were invalids. As the two crossed the little bridge over Valley Creek, they were deep in conversation. On the corner of the road stood a barn where Washington stabled a few horses. He states that Washington had promised one of the horses to Lafayette, so Lafayette invited Muhlenberg to go into the barn with him to see his prized gift. The conversation having stopped, Lafayette quietly opened the door. Suddenly they saw Washington kneeling on the hay in prayer, with closed eyes facing upward and hands clasped together and lifted toward Heaven. Muhlenberg reportedly expressed later that Washington’s face looked extremely sad. He uttered no words audibly. The story goes on to say that the men gently closed the door and walked silently for a ways. Their words were few on the rest of the way. Lafayette expressed that the experience assured him that prayer and the taking up of arms were compatible when the cause was just.

[The former pension agent’s account is quite long and detailed and quite dramatically written. It seems a little difficult to believe that anyone could have recalled so many details told to him some years earlier. I also noticed that the other accounts of Washington praying in the woods mentioned audible prayer, whereas this version says he did not pray audibly. It seems that if his habit was to pray audibly, he would do it consistently. And if he really went to pray in the shelter of a barn one night, isn’t it likely he would have gone there the other times, rather than kneeling outside in the cold? The Lafayette story may be a completely manufactured story, or possibly just embellished. But if the story did really happen, it seems to me it surely must be a completely different incident from the one in which Isaac Potts was said to have witnessed Washington in prayer. Knowing that General Washington was a man of frequent prayer and that the conditions at the Valley Forge camp were so desperate, it’s not hard to believe that he was observed in prayer in the woods more than once. Some historians have tried to totally discredit both of these stories, but I believe that the corroborating evidence for the Isaac Potts story makes it seem quite certain that it is true.]

What were the horrible conditions at Valley Forge?

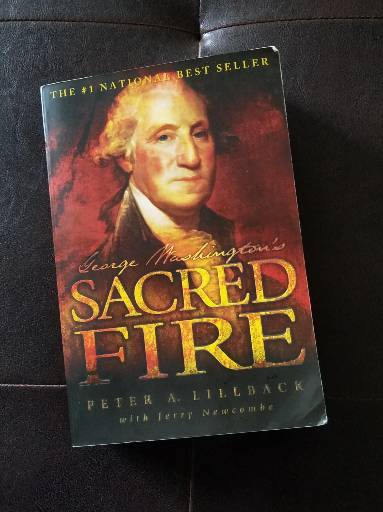

I wanted to know more about the awful conditions at Valley Forge that might move General Washington to find a place of prayer in the woods and call out to God. I suddenly remembered a 1,187-page book I had purchased a few years ago called George Washington’s Sacred Fire. (Not counting the pages comprising the vast sections of appendices and endnotes at the back, it was 725 pages.) It was written by Dr. Peter A Lillback, with Jerry Newcombe’s help. It was published in 2006, and the cover indicated that at one time it was “The #1 National Bestseller.” What a debt we owe Dr. Lillback and the man who assisted him, Jerry Newcombe. I can’t even imagine how many hours of research and writing it took to finish such a voluminous book. He spent 15 years doing research. He was careful to show his documentation very fully, as evidenced by the appendices and endnotes sections. He discussed the deterioration of historic truth in the first chapter. He mentions a Washington Times article reporting that “George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin were not included in the revised version of the New Jersey Department of Education history standards, a move some critics view as political correctness at its worst.” Although some early history teachings went overboard to make Washington appear perfect from childhood, now history is going too far the other way. Lillback states that one scholar, without giving any evidence, claimed that Washington didn’t even go to church. From reading Lillback’s book, it seems there are reams of evidence to the contrary. Lillback’s main point seems to be to show that George Washington was not a “Deist,” as some historians like to claim. I would say he “blew them out of the water.” Over and over he showed that the “Deist claimers” were either very shallow in their research or deliberately overlooked evidence. I didn’t have time to read the entire book before writing this article, but I scanned it and read certain chapters that I felt would be especially helpful in documenting the great faith of “The Father of Our Country.” You may want to read the book for yourself to discover many other interesting details about Washington’s life.

I wanted to know more about the awful conditions at Valley Forge that might move General Washington to find a place of prayer in the woods and call out to God. I suddenly remembered a 1,187-page book I had purchased a few years ago called George Washington’s Sacred Fire. (Not counting the pages comprising the vast sections of appendices and endnotes at the back, it was 725 pages.) It was written by Dr. Peter A Lillback, with Jerry Newcombe’s help. It was published in 2006, and the cover indicated that at one time it was “The #1 National Bestseller.” What a debt we owe Dr. Lillback and the man who assisted him, Jerry Newcombe. I can’t even imagine how many hours of research and writing it took to finish such a voluminous book. He spent 15 years doing research. He was careful to show his documentation very fully, as evidenced by the appendices and endnotes sections. He discussed the deterioration of historic truth in the first chapter. He mentions a Washington Times article reporting that “George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin were not included in the revised version of the New Jersey Department of Education history standards, a move some critics view as political correctness at its worst.” Although some early history teachings went overboard to make Washington appear perfect from childhood, now history is going too far the other way. Lillback states that one scholar, without giving any evidence, claimed that Washington didn’t even go to church. From reading Lillback’s book, it seems there are reams of evidence to the contrary. Lillback’s main point seems to be to show that George Washington was not a “Deist,” as some historians like to claim. I would say he “blew them out of the water.” Over and over he showed that the “Deist claimers” were either very shallow in their research or deliberately overlooked evidence. I didn’t have time to read the entire book before writing this article, but I scanned it and read certain chapters that I felt would be especially helpful in documenting the great faith of “The Father of Our Country.” You may want to read the book for yourself to discover many other interesting details about Washington’s life.

George Washington’s Sacred Fire gave some insight into the conditions of Valley Forge in the winter of 1777-78. General Washington described the Patriot army’s hardships. He stated that they lacked clothing, blankets, and shoes. There was a trail of blood in the snow, from the marching of shoeless soldiers. It was recorded that on December 18, 1777, plans were given for groups of 12 to build 14-foot by 16-foot huts out of logs, with fireplaces, for them to dwell in. On December 19th the army marched to Valley Forge. On the 20th they began to fell frees for huts and firewood. Surrounding farmers were commanded to give straw for the soldiers’ beds. On the 21st a model hut was completed. By New Years Day, many of the huts were finished, but not all were finished until February 7th.

There was also a shortage of clothing. They had to demand clothing from the civilians living in the countryside. They had to use clothing of British officers from a captured ship and clothing from soldiers who had died in the hospitals. There was no meat for the soldiers to eat, and the horses were starving for lack of foliage. Even the officers were tempted to steal fowl. Some of the soldiers suffered frostbite in their feet and legs and had to have them amputated. A shortage of blankets and straw caused sickness and death. The soldiers were three months behind in pay. They were on the brink of mutiny. There were civilians selling liquor on the edges of the camp. Prostitutes came in disguised as nurses. A hundred medical books for a British physician were captured, but Washington graciously had them returned to the British.

But there was SOME good news. Some Philadelphian women drove in ten teams of oxen to be slaughtered, and they brought 2,000 shirts they had sewn for the Patriots’ army, with the enemy right close by. Martha’s presence during the winter was helpful. And there was an occasional dance or play for entertainment.

What about the “Deist” claims?

What is a “Deist”? Lillback explains that the definition of Deism has changed over the years, but it has always meant that Jesus coming to earth as the Son of God is denied. He says that “hard Deists” not only refuse to believe that God has unveiled Himself through the Bible, but they also refuse to even believe that He intervenes in the events of history (as opposed to those who use the word “Providence” to indicate their belief in God’s intervention). Lillback also informs us that many believe Washington to be a “soft Deist.” That would mean that he did believe in God’s intervention in history, but he didn’t believe that God was revealed in Scripture, nor did he believe in Christ’s divine nature, His atonement for our sins, or His resurrection. Washington’s use of the word “Providence” shows his belief that God intervenes in history. He used the word “heaven” more than a hundred times. He used the word “God” more than a hundred times, but he also liked to use other descriptive titles for God, such as “the Great Author of the Universe” or the “Great Disposer of Human Events.” This doesn’t mean he was a Deist, who believed that God was only a distant entity who created the world and influenced history. Ministers of Washington’s time commonly used these creative titles to honor God. Evidence provided in this book will remove all doubt that Washington highly valued the Bible and believed in the doctrines of the divinity of Christ. Though I had assumed that the determination to label all the Founding Fathers as Deists began in recent years, I was surprised to discover that the accusations that Washington was a Deist began way back in the 1920s.

Evidence of Washington’s Christian Beliefs

Washington was a lay leader in his church, which required him to take an oath that he affirmed central doctrines of the Christian faith. Some of these doctrines were that Christ was both God and man, that Christ died to pay for our sins, that He rose from the dead, that He is now in Heaven at God’s right hand, that Christ will return to earth, that the Bible is God’s Word, and that sinners must repent and believe in Christ in order to receive salvation. While Washington was president, he and his wife Martha attended the Sunday service at Christ Church, unless the weather was unusually bad. Sunday evenings George read a sermon or Scriptures to Martha in her chambers.There are many anecdotes of Washington reading the Bible in his home or in his military quarters. There are over two hundred allusions to Scriptures found in his writings.

Washington regularly used and shared the 1662 Book of Common Prayer used by the Anglican Church. It was very theologically orthodox. He ordered a pocket-size edition, in order to be able to have it with him. There are more than a hundred expressions of prayer found in his many letters.

ordered a pocket-size edition, in order to be able to have it with him. There are more than a hundred expressions of prayer found in his many letters.

There is a record of a conversation with General Porterfield, which states: “He said that his official duty (being brigade inspector) frequently brought him in contact with General Washington. Upon one occasion, some emergency (which he mentioned) induced him to dispense with the usual formality, and he went directly to General Washington’s apartment, where he found him on his knees, engaged in morning devotions. He said that he mentioned the circumstance to General Hamilton, who replied that such was his constant habit.”

It is recorded that Washington had ordered the military troops under him to refrain from cursing and swearing. It wounded him to hear the Names of the one who gives all the blessings of life disrespected. He called it “wicked and shameful.”

The fact that Washington was a slave holder has been used as ammunition against him. Most of Washington’s slaves were inherited. Because of the laws of his time, freeing slaves was a complicated issue. I discussed the issue in more detail in a “Thoughts” article for July 4th of 2020. Lillback’s book records a statement by Washington to Lawrence Lewis: “I wish from my soul that the Legislature of this State could see the policy of a gradual Abolition of Slavery.”

In addition to the above evidence, Dr. Lillback records a very significant comment about Washington that was written in the notebook of a German Lutheran clergyman by the name of Rev. Henry Melchoir Muhlenberg: “I heard a fine example today, namely that His Excellency General Washington rode around among his army yesterday and admonished each and every one to fear God, to put away wickedness that has set in and become so general, and to practice Christian virtues. From all appearances General Washington does not belong to the so-called world of society, for he respects God’s Word, believes in the atonement through Christ, and bears himself in humility and gentleness. Therefore, the Lord God has also singularly, yea, marvelously preserved him from harm in the midst of countless perils, ambuscades, fatigues, etc., and has hitherto graciously held him in his hand as a chosen vessel.”

The Communion Question

Those trying to prove that Washington was a Deist have tried to prove he did not participate in communion. Those who recognize his participation in communion services most of his life make an issue of the apparent lack of participation in communion in his later life. They assume that lack of participation in communion later in life could indicate that he turned into a Deist and no longer believed in the atoning work of Christ. I will give evidence, from Lillback’s book, of his attendance at communion most of his life and some very logical reasons why he may not have attended in later life.

Those trying to prove that Washington was a Deist have tried to prove he did not participate in communion. Those who recognize his participation in communion services most of his life make an issue of the apparent lack of participation in communion in his later life. They assume that lack of participation in communion later in life could indicate that he turned into a Deist and no longer believed in the atoning work of Christ. I will give evidence, from Lillback’s book, of his attendance at communion most of his life and some very logical reasons why he may not have attended in later life.

It was consistently reported that Washington attended communion before the Revolution. There are accounts of his partaking of communion in a Presbyterian church in Morristown, New Jersey, during the Revolutionary War. In the week before their semi-annual communion celebration, Washington rode to the pastor’s home to ask whether a non-Presbyterian could partake. The pastor informed him that all denominations were welcome. The Presbyterian Magazine reported that the congregation met that day in an orchard. The article specifically mentioned that Washington took of the bread and wine. The magazine also explained why they were meeting in an orchard. Because of a smallpox epidemic, courthouses and Presbyterian and Baptist churches were being used as hospitals.

At a family reunion in New York in 1854, Mrs. Alexander Hamilton, Sr., shared the story of Washington taking communion at St. Paul’s on his inauguration day in 1789. [New York served as the capital from 1785 to 1789.] She told her great grandson she had knelt beside Washington at Holy Communion. She also told him of being at Valley Forge with her father, who was a general. She had heard Washington pray earnestly for the well-being of the soldiers.

Major Popham served with Washington during the Revolutionary War. He testifies to having attended the same church as Washington, St. Paul’s, while Washington served as president in New York. He sat in the pew next to George’s pew. He remembers often kneeling beside Washington at the communion table.

In 1793 Washington had to leave Philadelphia because of a yellow fever epidemic, and he stayed with a pastor in Germantown. [The capital was moved back to Philadelphia from 1790 to 1800.] Tradition says that Washington attended the Reformed Church there and took part in communion there once. [This would be at the beginning of his second term as president and only about six years before his death. This would seem to me to indicate that his reason for not attending communion in his later years likely had to do with issues related to observance of communion in his own church, rather than observance of communion in general.]

As stated earlier, it appears there were periods of time in Washington’s later life when he did not partake of communion. An incident was said to have happened while Washington and his family were regularly attending Christ Church, an Episcopal church under the leadership of Bishop William White. This was while Washington was serving as president and sessions of Congress were held in Philadelphia. Washington and his family attended a service wherein Dr. Abercrombie preached a sermon condemning not participating in communion on Communion Sunday. From then on Washington did not come to the service at all on Communion Sundays. Washington’s granddaughter said that on Communion Sundays she left with her grandfather after the regular service and before the communion service. The carriage was returned to pick up her grandmother later. Bishop White believed that Washington took Dr. Ambercrombie’s comments to mean that it was disrespectful to leave before communion, so he did not attend on Communion Sundays, in order not to appear disrespectful. Those who claim Washington was a Deist say this proves he didn’t believe in Christ as our atonement.

There are some circumstances that make very reasonable arguments for why Washington may not have wanted to attend the communion services later in his life. For one, the Anglican church where he attended before the war gave honor to the King of England. On his return from the Revolution, he wrote to the church saying he could no longer be a lay leader there. The service for Communion in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer included two prayers for the King of England. (The church later became an Episcopal Church, and the prayers for the King in the Book of Common Prayer was replaced by prayers for the president and Congress.) The combination of Loyalists and Patriots in the church had also caused tension in friendships.

Another possible factor in Washington’s lack of attendance at communion was the length of the service. In the late 1780s, the Episcopal Church had communion three or four times a year. The Morning Prayer Service was 12 pages long, and then there was a full-length sermon. The Communion Service was another 26 pages long, not to mention the time it took to partake of the wine and bread. Most of the congregation left before the Communion Service. No doubt it would have been difficult for his 12-year-old granddaughter and 10-year-old grandson. [George and Martha took them into their home in 1781, when their father died.] Also, Washington had great demands on his time. In his later years, before he retired, Sunday afternoon was his only time to try to keep up with a great amount of personal correspondence and deal with problems at the Mount Vernon plantation.

There may be yet another reason for Washington’s lack of communion participation. There was a struggle going on in the American Episcopal (formerly Anglican) Church. There was “High Church” and “Low Church” doctrine. The High Church members believed that the Bishops must come through a continuous succession from the apostles. They also frowned upon participating in services of other denominations. Washington was a firm believer in the Low Church (sometimes called “Broad Church”) doctrine. In 1785, Bishop Seabury was ordained to lead Washington’s church. Not only was Seabury of the High Church, but he had been loyal to the British and very critical of the American Revolution. He believed that the communion celebration was not valid unless performed by someone with an unbroken line of succession from the apostles. Eventually, the Low Church leaders compromised with the High Church leaders who were loyal to England, leaving the Low Church members and supporters of the Revolution at a disadvantage.

The Masonic Lodge Question

Washington’s membership in the Masonic Lodge has been further fuel for claiming he was a Deist. At age 20 he joined the Fredericksburg Lodge. When sworn into office as president, he swore on the Masonic Bible.

But some telling evidence in the different nature of the Masons when Washington joined is the fact that he had sermons in his library that had been preached at the invitation of the Masons. They were sermons by orthodox evangelical clergymen.

Here is an excerpt from a sermon preached to the Masons by Rev. Dr. William Smith on December 28, 1779:

“Such conduct becomes those who profess to believe that when our Master Christ shall come again to reward his faithful workmen and servants; he will not ask whether we were of Luther or of Calvin? Were we prayed to him in white, black, or grey; in purple, or in rags; in fine linen, or in sackcloth; in a woolen frock, or peradventure in a Leather-Apron? Whatever is considered as most convenient, most in character most for edification, and infringes least on Spiritual liberty, will be admitted as good in this case. But although we may believe that none of these things will be asked in that great day; let us remember that it will be assuredly asked—were we of CHRIST JESUS? ‘Did we pray to him with the Spirit and with the understanding?’ Had we the true Marks of his Gospel in our lives?”

[The punctuation and wording is a bit confusing, but you get the drift. I’m not certain if it is solely because of archaic grammar rules or errors by the minister who wrote it, or a little of both.]

On September 25, 1798, Rev. G. W. Snyder wrote to Washington and sent a book called Proofs of Conspiracy, which warned that an anti-religion and anti-government organization called the “Illuminati” had infiltrated American Mason fraternities. Washington responded that he had only been in a lodge once or twice in the last 30 years, but he didn’t believe the Lodges in America had been “contaminated” by the Illuminati. In a 1798 sermon, the president of Yale College wrote that the original Masonic purpose of friendship and fellowship were being sidestepped and “the aims against government, morals, and religion were elevated.” But until close to the early 1800s the Masons were mainly, though not exclusively, made up of orthodox Christians.

Did God Respond to Washington’s Prayers?

Before the colonists could no longer tolerate the British rule, they fought with the British in the French and Indian War. God was already watching out for Washington. Washington had tried to warn General Braddock of the fighting techniques used by the Indians, but he didn’t listen. Consequently, in one particular battle the French and Indians only lost three officers and 30 men, while the colonists and British had 714 either killed or injured. Colonel Washington was the only officer on his side of the battle to be left alive. Here are some words from a letter he wrote to his brother after the battle: “ . . . I now exist and appear in the land of the living by the miraculous care of Providence, that protected me beyond all human expectation; I had 4 bullets through my Coat, and two horses shot under me, and yet escaped unhurt.”

In one of the skirmishes of 1776 in the Revolutionary War, Washington and his army were trapped on Brooklyn Heights, Long Island. Washington decided to try a brave maneuver. With fog as their cover, he removed the troops during the night. He had to use every ship he could find—from fishing boats to rowboats. In the morning, the fog stayed much longer than usual. It stayed just long enough so that all of Washington’s troops were able to cross the river and find safety. (General Cornwallis tried to use the same technique for his British troops in Yorktown in 1783. But for them there was no fog to help conceal them, and a squall even came up on the Atlantic Ocean. Their escape was a dangerous failure. Cornwallis ended up having to surrender the next day.)

After Benedict Arnold, whose name has become another word for “traitor,” nearly delivered an important American post—West Point—into the hands of the British, these words were written: “Happily the treason has been timely discovered to prevent the fatal misfortune. The providential train of circumstances which led to it affords the most convincing proof that the Liberties of America are the object of divine Protection.”

Here is a portion of a description of the Battle of Cowpens that took place on January 17, 1781: “Cornwallis regrouped and chased the Americans, arriving at the Catawba River just two hours after the Americans had crossed, but a storm made the river impassable. He nearly overtook them again as they were getting out of the Yadkin River, but a torrential rain flooded the river. This happened a third time at the Dan River.”

If time and space allowed in this article, more stories could be told. Here is an excerpt from a letter from Washington to Major General Nathaneal Greene on February 6, 1783: “. . . it is more than probable that Posterity will bestow on their labors the epithet and marks of fiction; for it will not be believed that such a force as Great Britain has employed for eight years in this Country could be baffled in their plan of Subjugating it by numbers infinitely less, composed of Men oftentimes half starved; always in Rags, without pay, and experiencing, at times, every species of distress which human nature is capable of undergoing.” [One earmark of Washington’s writing was that he tended to randomly capitalize words.]

In 1789 Washington again confirmed his certainty that God had intervened for America. He wrote: “The man must be bad indeed who can look upon the events of the American Revolution without feeling the warmest gratitude towards the great Author of the Universe whose divine interposition was so frequently manifested in our behalf.”

Following the Example of the Father of our Country

After reading Lillback’s book, George Washington’s Sacred Fire, there is no doubt in my mind that George Washington was a man of great faith. Our nation is once again in deep trouble. Will we follow the example of “The Father of Our Country” and cry out to God to help us in this time? II Chronicles 7:14 tells us that before God will hear our prayers we must humble ourselves (as Washington did) and turn from our wicked ways (follow the teachings of Scripture, as Washington did). I Timothy 2:1-2 tells us to pray for all those in authority, so that we can live peaceful, godly lives. We are to pray for ALL those in authority. I guess that means even the ones we believe are doing all the wrong things and we feel like giving up on.

Will we have the same courage and determination that Washington had when he led his troops to march through the snow with bare, bleeding feet and shabby clothes? The leaders of Israel often asked for God’s help, as Washington did. But the Israelites still had to go out and fight the battles, as Washington and his men had to do. Even when the walls of Jericho fell without a fight, the Israelites had to march around the walls seven times and blow their trumpets in obedience to what God had told them to do. We are not in a physical fight right now. We are in a spiritual battle, but there is much we can do. We may have to sacrifice time or money to take righteous stances. It may require speaking what we believe to be the truth when it isn’t popular, writing letters or e-mails to our leaders (including words of appreciation when we feel they are serving well), refusing to support companies with evil agendas, homeschooling, disobeying laws if they conflict with God’s laws, volunteering to help righteous candidates, or maybe even running for precinct committee person or school board member or some other office for which we are qualified. We need to do whatever it is we feel God is asking of us. Whether or not we are willing to “fight” the spiritual battle is an indication of our loyalty. I read online that there was never more than about 45% of the colonists who were on the side of fighting for freedom, and sometimes they switched sides, depending on who was winning.

Below is a famous inspiring hymn that was written in 1876, to celebrate the centennial of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The last verse asks of God, “Refresh thy people on their toilsome way. . .” That seems to be an appropriate prayer for these times.

VIDEOS SUGGESTED AT THE END OF THIS VIDEO ARE NOT NECESSARILY ENDORSED BY THIS WEBSITE

Leave A Comment